Big Ideas & Philosophies

- Marea Maloney

- Oct 29, 2021

- 9 min read

Updated: May 4, 2022

Study group: Me, Me Me: An exploration of the Self

Big Ideas and Philosophies:

Maréa Maloney

Unit Code: C18201

Motion Graphics, MGR

10th December 2021

List of Illustrations:

Fig.1: Berlin, Jesse (2018) Denizen of the Uncanny Valley 2 [Sculpture, Stoneware]

(Accessed: 08 December 2021)

Fig.2: Zemeckis, Robert (2004) Polar Express [Film]

Fig.3: Multiple Sources (2021) Liminal Spaces. Pinterest [Online Search]

Available at: www.pinterest.co.uk/search/pins/iminal spaces

(Accessed: 09 December 2021)

Fig.4: Mori, Masahiro (1970’s) Uncanny Valley Graph [Online]

(Accessed: 08 December 2021)

Unravelling the Uncanny Valley

The Uncanny Valley is a concept in art which describes the strange and anxious feeling sometimes created by familiar objects in unfamiliar contexts. We will be unravelling the uncanny – looking further into how the theory is rooted in everyday experiences and the aesthetics of popular culture; related to what is frightening, repulsive and distressing. This text will be focusing on the human-like appearance of inanimate figures, and how the theories associated with the uncanny valley have been developed over time; specifically relating to recent technological advancements regarding animation and CGI within film & TV as well as the rise in robotics and artificial intelligence.

The term was first used by German psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch in his essay ‘On the Psychology of the Uncanny’ (1906). Jentsch describes the uncanny as something new and unknown that can often be seen as negative at first. However, this idea was further developed by Sigmund Freud, and it has now been over 100 years since Freud wrote his paper, ‘The Uncanny’ (1919). This paper explores the words ‘heimlich’ and ‘unheimlich’ (or ‘homely’ and ‘unhomely’, as it directly translates into English). Freuds repositioned theory describes the uncanny as the instance when something can be familiar yet alien at the same time. He suggested that ‘Unheimlich’ was specifically in opposition to ‘heimlich’, which can mean homely and familiar, but also secret and concealed. Therefore ‘Unheimlich’ was not just the unknown, but also bringing out something that was hidden or repressed. Freud’s paper tackles people, things, self-expressions, experiences and situations that best represent the uncanny feeling, as well as horrific concepts of inanimate figures coming to life.

“For this uncanny is in reality nothing new or alien, but something which is familiar and old-established in the mind and which has become alienated from it only through the process of repression.” – Sigmund Freud (1919)

Though the phenomenon was only developed in the last century, ideas of the uncanny valley can be traced back more than 2,000 years, to classical antiquity. The most ancient examples of an uncanny valley response to artificial life can be found in Homers ‘Odyssey’ (ca. 700BC) when, in the underworld, Odysseus jumps back in fear when he encounters vivid pictures of ferocious wild predators and murderers with glaring eyes. Odysseys hopes that the artist will not create any more of these terrifying images.

Many artists, specifically associated with the surrealist movement, drew inspiration from this idea and made artworks that combined familiar things in unexpected ways to create uncanny feelings. The representation of human beings is portrayed through many different forms, and lends itself to art, literature and cinema; but it is when these depictions become so realistic that they become unsettling, but not realistic enough to engender likeability, when the uncanny valley is present.

American sculptor, Jesse Berlin created a series of sculptures to envision the uncanny valley, not as a mathematical concept, but rather a location in the subconscious inhabited by beings distorted, yet disturbingly familiar.

Figure 1 (2018) Denizen of the Uncanny Valley 2. Jesse Berlin [Sculpture]

Another point that Freud touches upon is the notion of ‘the double’ or ‘the doppelganger’, first explored in the psychoanalytic literature by Otto Rank in 1914. Freud writes that doppelgangers can be found in “mirrors, shadows, guardian spirits,with the belief in the soul and fear of death. The idea of the eternal soul allows us an energetic denial of the power of death. This was the first double of the body, from having been an assurance of immortality, it becomes the uncanny harbinger of death.” This doppelganger effect is represented in several subculture references. Stanley Kubrick’s cinematic horror adaptation of Stephen King’s ‘The Shining’ is a perfect example. An eerie mansion, said to be haunted by people who have died, whose mangled figuresstill appear in the grounds where they were murdered. These are doubles, alternate

versions of themselves. We see them moving, but are they dead or alive? Many people experience the uncanny to its highest degree with death, dead bodies and the return of the dead, and Freud’s theory essentially hypothesized that it all comes down to death. This fear stems from the reality that nobody has a complete understanding of their own mortality. Through this process, we can see that the nature of the uncanny is entirely subjective, based upon our own experiences but haunts each of us to a varying degree.

In the current day, the term ‘uncanny valley’ is also applied to artworks and animation in film and TV that reproduce people and places so closely that they create a similar eerie feeling. The standards of motion picture technology in the modern age have reached staggering heights, showcasing visuals so impressive that the cinema of the 20th century would not even be able to comprehend it. From the early stop-motion artistry of Ray Harryhausen to the pioneering efforts of John Lasseter at Pixar, animation and computer-generated imagery (CGI) has come a long way. But in some cases, the animation and special effects have got so advanced that they begin to look so realistic that it passes the point of comfort and falls into the uncanny territory. Our brains can register that the character is very close to human, but we are also aware that something is not quite right. It is the in-between where we can process that something looks like a person, although it is not, and causes feelings of distress.

My favourite examples of CGI and AI, in the world of film and TV in relation to the uncanny valley is Alex Garland’s, Ex Machina (2014). For me, the most fascinating element of the film is Alicia Vikander’s (AVA’s) movements. Garland stated that Vikander has the ability to make “The perfect version of human movements”, which results in the creation of a living version of the uncanny valley. And the fact that we know Ava is a robot, makes this one of the film’s most haunting effects. She moves with such precision; we can see her mechanical frame and yet it is so easy to confuse her with a real person.

This uncanny feeling is also frequently shown through animation and different methods of character design. One of the most well-known modern examples of this is actually an early test screening of the animated film Shrek (2001), where Fiona was rendered in a very hyper-realistic style of animation - so realistic that it surpassed the threshold of comfort and cartoon and moved into the uncanny valley. It was reported that children who attended the test screening became so panicked that they were said to be crying anytime she appeared on the screen. This led to the entire film being halted so that Fiona’s character could be re-rendered to become the family-friendly film we all know today.

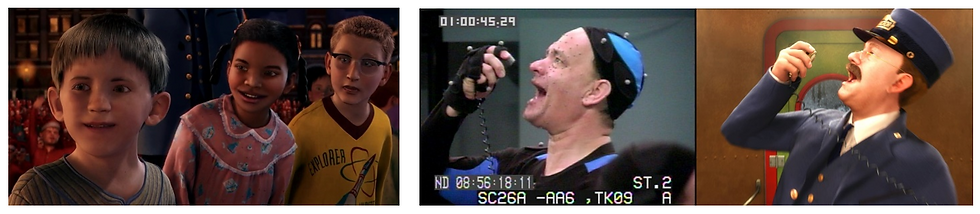

Another common example of the uncanny valley being represented through animation in films is in the classic Christmas film, Polar Express (2004). Director, Robert Zemeckis introduced a brand new motion capture method of live-action CGI for the film adaptation of the original book by Chris Van Allsburg. Zemeckis opted to use this new filmmaking technique as he believed that “live-action would look awful, and it would be impossible”. Unfortunately, Zemeckis was wrong, and by using this new method of live-action CGI, he ended up creating “one of the worst looking cinematic disasters of all time”.

Taking a trip down the infamously horrifying uncanny valley, the Polar Express struggles to depict the real-life emotions and facial expressions of a human character, instead, settling for low quality renders that suggest nothing behind the lifeless eyes of the main cast. Though the animation does a reasonable job at recreating objects, landscapes and even fantastical creatures, it has a lot of trouble recreating human facial expressions, resulting in weird, unpleasant and unsettling consequences as a computer tries to replicate accurate and existing elements.

Figure 2 (2004) Polar Express. Robert Zemeckis [Film]

This same uncanny aspect can be seen in the early works of Pixar, who seemed to master the animation of animals, fantastical toys and other bizarre elements, though often struggled with human characters, in the likes of Toy Story, Monsters Inc, Finding Nemo, etc… The early 2000s was a transition period for animation and although many films released around this time struggled to portray hyperreal, CGI faces, viewers were still thrilled to see new 3D technology at work and could only imagine where the industry would go from there. And luckily, these films were just a starting point for animation design.

We often feel the same feeling of distress when looking at images of liminal spaces - places that appear to be familiar, but you know you have never actually been there before, which leaves you feeling incredibly uneasy. These locations are a transition between two other locations, or states of being, typically, abandoned and often times empty. This makes it feel frozen and slightly ominous, but also familiar to our minds. The liminal space aesthetic refers to the distinct and mixed feeling of eeriness, nostalgia, and apprehension we get when presented with such places outside of their intended contexts. For example, an empty stairwell, playpark or hospital corridor at night may appear as sinister or uncanny because these places are usually brimming with life and movement. Therefore, the absence of this (people, movement, conversations, or any kind of dynamism) creates an otherworldly and forlorn atmosphere and a sense of derealisation within our minds.

Figure 3 (2021) Multiple sources, Liminal Spaces. Pinterest [Online Search]

Although Jentsch & Freud initially established the theory in the early 1900s, it was Masahiro Mori, a professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, who related the uncanny valley concept to humanoid robots and lifelike computer-generated characters. Mori used the term Uncanny Valley in an article for the Japanese journal, Energy (1970) to describe his observation that as robots appear more humanlike, they become more appealing – but only up to a certain point. When we reach the uncanny valley, we have a sense of strangeness, unease, and a tendency to be scared or freaked out. This cognitive dissonance produces an eerie sensation, followed by the realisation that the object is in fact artificial. So, Mori’s hypothesis suggests that the uncanny valley can be defined as people’s negative reaction to certain lifelike robots.

Mori also introduced the uncanny valley graph (Fig.4) This graph depicts that, as a robots human likeness (horizontal axis) increases, our affinity towards the robot (vertical axis) increases too, but only up to a certain point. For some lifelike robots, our response to them plunges, and they appear repulsive or creepy, and that’s when the uncanny valley is reached.

Figure 4 (1970’s) Uncanny Valley Graph. Masahiro Mori [Online]

Despite our fascination with the uncanny valley, its effectiveness as a scientific concept is still challenged. The uncanny valley has often been criticized as a scientific concept and is regularly considered to be more of a pseudoscience – consisting of statements and beliefs that claim to be both scientific and factual, but incompatible with the scientific method. Mori himself said in an interview with IEEE Spectrum, that he didn’t explore the concept from a rigorous scientific perspective but as more of a guideline for robotic designers: “Pointing out the existence of the uncanny valley was more of a piece of advice from me to people who design robots rather than a scientific statement”. This idea can also be applied to other art forms, including art, literature and cinema.

The uncanny valley is still a widely unstudied phenomenon, but it continues to become more and more pervasive in everyday life and is believed to be an evolutionary mechanism, not exclusive to just humans. The rise of robotics, AI, special effects and CGI are all constantly evolving and along with it, the uncanny valley. With the ever-advancing technology, it is interesting to think about how this theory will be perceived in the future. Will we be able to distinguish a stable midpoint between things that are inherently artificial and things that are inherently human without being left with feelings of distress?

Bibliography:

Ruers, Jamie (2019) The Uncanny.

Available at: www.freud.org.uk/2019/09/18/the-uncanny

(Accessed: 26 November 2021)

Jentsch, Ernst (1906) On the Psychology of the Uncanny [Paper]

Freud, Sigmund (1919) The Uncanny [Paper]

Tate (Date Unknown) Art Term: The Uncanny.

Available at: www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/t/uncanny

(Accessed: 26 November 2021)

Mayor, Adrienne (2018) The Uncanny Valley in Ancient Greek Art. Time.

Available at: www.time.com/5452383/uncanny-valley-ancient-greece

(Accessed: 26 November 2021)

Berlin, Jesse (2018) Denizen of the Uncanny Valley 2 [Sculpture, Stoneware]

(Accessed: 03 December 2021)

Caballar, Riba Diane (2019) What is the Uncanny Valley. IEEE Spectrum.

(Accessed: 05 December 2021)

Shrek (2001) Directed by Vicky Jenson and Andrew Adamson [Film] Place of Distribution: DreamWorks Pictures

Polar Express (2004) Directed by Robert Zemeckis [Film] Place of Distribution: Warner Bros. Pictures

Ex Machina (2014) Directed by Alex Garland [Film] Place of Distribution: A24

Tucker (2013) The Uncanny Valley. The Art Blot.

Available at: www.artblot.wordpress.com/2013/11/25/the-uncanny-valley

(Accessed: 03 December 2021)

Russel, Calum (2021) The disturbing uncanny valley of Robort Zemeckis film ‘Polar Express’. Far Out.

(Accessed: 05 December)

PDF Download of Submission:

Comentarios