The Rise, Fall and Revival of Blackletter: Exploring the Resurgence of the Historic Script

Maréa Maloney

Ravensbourne University, London

Motion Graphics

2022/2023

Introduction

After years of being shunned by designers, one of the oldest scripts in the history of typography has made a comeback. Blackletter, as a typographic family, was created at the birth of European printing to emulate the writing of scribes who had previously copied books by hand. This dissertation will delve deep into the world of blackletter typography, exploring the history and creation from its calligraphic background, why it fell out of favour during the second World War and how contemporary designers and the rise of digital technology have led to a revival of the typestyle.

To accompany the analytical text, I will be designing my own iteration of the classic font. A typeface that will remain true to its typographic roots by considering the original principles of design from its conception in the Middle Ages while also preserving the key elements that make up the font. I want to show how a modernisation can positively impact the contemporary design world and remove any negative connotations that the typestyle held in the past.

History of Blackletter

What is Gothic? Gothic was the culminating artistic expression of the Middle Ages, occurring from roughly 1200 to 1500 Century AD. The term ‘Gothic’ originated with the Italians who used it pejoratively to refer to the gothic tribes and barbaric cultures North of the Italian Alps. The style developed from Romanesque Art in the 12th Century, led by the concurrent development of gothic architecture, but it was strongly criticized when it was first introduced. Critics saw it to be unrefined and too far from the aesthetic proportions of classical art, triggering the demise of the classical world, along with all the values it held. The gothic style soon began to spread across western Europe, and although it was eventually popularised and became a recognised art form, some people still weren’t too keen. Italian artist and writer, Giorgio Vasari, called it a “Monstrous and barbarous disorder” (Vasari, 1511-1574) and French playwright Molière famously commented on Gothic saying:

The besotted taste of gothic monuments,

These odious monsters of ignorant centuries,

Which the torrents of barbary spewed for

(Molière, 1622-1673)

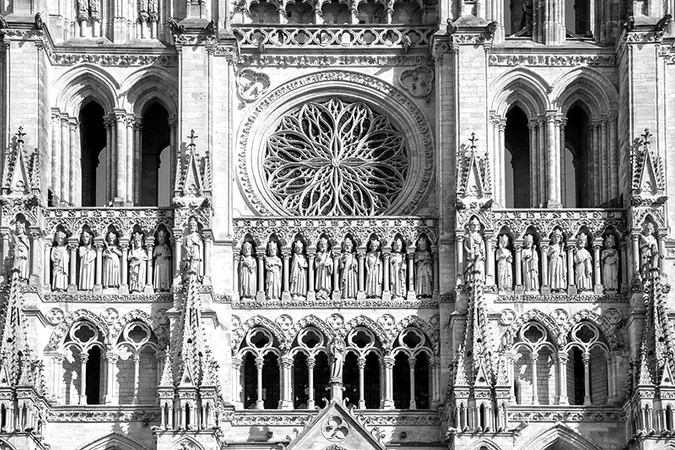

A large proportion of art produced in this period was religious, meaning gothic art was often typological in nature - bringing a sense of realism and natural humanity to art. The most notable pieces of the time were monumental and portable sculptures commissioned by the laity, with both Old and New Testament scenes being depicted in decorations of churches. French gothic masterpiece, The Cathedral of Notre Dame, has numerous examples of this. The western façade of the Cathedral is enhanced by the infamous Great Rose decoration, but when looking closer, we are greeted by the many intricacies of the sculptures – the decorative gable piece showing the Litanies of Mary, the Kings’ Gallery, and the Portal of Last Judgement, depicting Christ as the centrepiece enthroned by angels.

Figure 1-2: Authors photographs of Notre Dame Cathedral, close detail of the decorative western façade.

The gothic style rapidly spread beyond its origins in architecture and began to appear in a variety of different forms, including stained glass, manuscripts, illustration, and other decorative arts.

The Illuminated manuscripts represent the most complete record of gothic illustrations, providing an archive of styles in places where no monumental works have otherwise survived. The earliest full manuscripts with gothic influence date to the middle of the 13th Century - a period which saw churches and universities flourish, greatly increasing the demand for books. The opportunity to create secular professional scribes benefitted both men and women, but history shows that women, especially nuns, have a long heritage in calligraphy, where they were more accepted than in type founding. With more people learning to read and write, came a need for a common hand-lettering style, which consequently led to the birth of blackletter typography. The linear structure and angular form of the characters were considered practical to the monastic scribes copying out entire books by hand, allowing them to write more rhythmically and correctly than rounded forms.

Figure 3-4: Illuminated Manuscript. The Psalter and Book of Hours of John Duke of Bedford.

Due to its creation in the gothic period, Blackletter type is often misleadingly referred to as either Gothic Script or Old English - two terms that have become synonymous with blackletter and can be used interchangeably but are only partially accurate. ‘Old-English’ was the language of the Anglo-Saxons until the mid-1100’s and they had nothing to do with blackletter. It was centuries after its initial emergence when Monotype created the font “Old English Text”, designed to mimic 11th-century calligraphy. And as we’ve already explored, ‘Gothic’ is the term used to describe the leading art movement and architectural style during the medieval times, a major influence for inspiring blackletter.

Blackletter itself, is an all-encompassing term used to describe the scripts of the Middle Ages - in which the darkness of the characters overpowers the whiteness of the page.

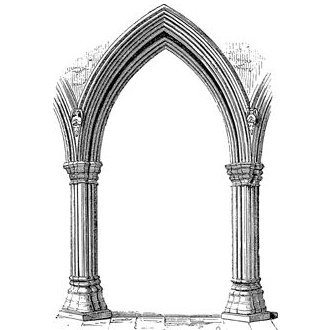

Blackletter is heavily inspired by the aesthetics of gothic stylisation; a distinctive style which looks very ornate and distinguished – almost as if it was created for the sole purpose of turning letterforms into individual flourishes of art. The typestyle is characterized by tight spacing and condensed lettering, with dark, saturated, calligraphic letters that are defined by dramatic strokes and elaborate serif swirls. Gothic architecture, once again, played an integral role for influencing this – the ogival-shaped arches, sharply pointed spires and ornate decorations are just a few examples of the coherence of gothic expression. Robert Bringhurst stated in his Elements of Typographic Style (Bringhurst, 1992) that ‘Blackletter is the typographic counterpoint to the gothic style in architecture’ – This can be seen through the pointed, angular appearance of the letterforms, along with the evenly spaced verticals that dominate them.

Figure 5: Illustrated architectural ogival arch with gothic influence.

Figure 6: Authors own illustrated depiction of architectural influence on typography.

These similarities came to life as the scribes would draw inspiration from their surroundings, and with religion holding a profound importance during this period, the architecture and art associated with churches would have been their main source of artistic intake. The scribes were emulating the styles they were familiar with in their handwriting and calligraphy, consequently intertwining two opposing art forms: typography and architecture.

Back then, just as now, readers valued standardization in a text. Every letter, even the rounded ones, had to look exactly the same. It was hard for a scribe copying out a text to consistently draw perfect circles over and over again and it was a lot easier to produce all those O’s, U’s and C’s out of a series of short straight lines instead of curves. Scribes were desperately seeking for a sustainable & efficient method to reproduce the letterforms, and luckily for them, in the 14th Century, mechanical printmaking was introduced to Europe.

Johannes Gutenberg played a crucial role in the world of movable type. His invention of the Gutenberg Press, along with the mechanized type that followed, revolutionised handwritten manuscripts in the late medieval times and is still relevant to modern typeface design and printing to this day.

Gutenberg is best known for his publication of the 42-line Bible, also known as the Gutenberg Bible, which showcased the necessity of a functional, readable typeface. His creation single-handedly led to the birth of modern typography - along with all the errors and bad kerning mistakes that came with it - but Gutenberg knew this was not the end for handwritten scripts and didn’t seem to have wanted to break off with the scribal traditions. For him, it was all about speeding up the process and shaping the future of typography – focusing on automation, consistency, and recycling rather than the aesthetics or design.

Figure 7-8: Johannes Gutenberg 42-line Bible and accompanying letterforms (Donatus-Kalendar).

Gutenberg’s letterforms were influenced by the liturgical scripts of the era - forms of blackletter type, characterized by tight spacing and condensed lettering, which helped to reduce the materials used in the printmaking process. The specific style of blackletter that appears in the Gutenberg Bible is called Donatus-Kalender – recognisable by its dramatic thin and thick strokes, some elaborate swirls on the serifs and the impression of texture that it creates across the page.

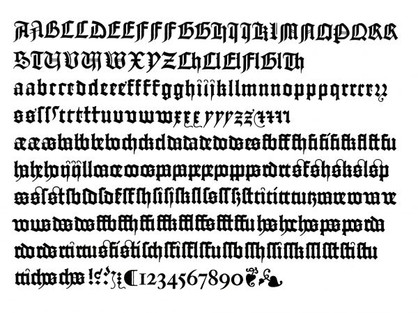

Blackletter had become the standard throughout Europe. So much so that it wasn’t really a type choice, it was just what words looked like. It became so ingrained in the culture that even after it stopped being needed, people kept using it. With so many big leaps in technology, the printing press started off by relying heavily on the design conventions that came before it, even though the new operating principles made those conventions unnecessary. Over time, a wide variety of different blackletters appeared, but four major families can be identified: Textura, Rotunda, Schwabacher and Fraktur. Other styles have become hybridized developments from one or more of these core styles.

Figure 9: Four major blackletter font families.

Although there are no standardized forms when it comes to these variations of blackletter, making it difficult to establish a holistic understanding of them, there is, however, definitive distinctions that can be made between each style. Consider a serif typeface, there isn’t one foundational serif, but instead, countless variations that fall into this extensive category. Understanding the qualities that this category is comprised of gives us the ability to distinguish whether or not it is in fact a serif typeface. Blackletter can be thought of in the same way. Once you understand the aesthetic qualities of the aforementioned styles, telling them apart becomes easy. Instead of noticing their differences, we can understand each one as an individual at its core.

Blackletter is a highly transferable typestyle. Despite it being incredibly distinct, it has a wide and diverse range of design formats it can take, especially the capitals. They can be ornate and lavish when used alone, or, when combined with lowercase letters in passages of text intended to be read, rather than merely gazed at, they can be subdued.

It reigned as the dominant typeface in Europe for several generations and it stayed that way until the end of the 15th Century. Printmakers found that blackletters were difficult to read as body text, and subsequently, roman typefaces were easier to print with – and for these reasons, blackletter gradually became less popular for printing in many countries except Germany and areas under German influence.

Why it fell out of favour

Germany continued to use blackletters until the early twentieth century, when German designers considered it to be antiquated and it finally fell out of favour. Blackletter was quickly replaced by a new era of typography, consisting of tall, bold, and slanted sans serifs, inspired by the notable characteristics of the Bauhaus art movement. But in 1933, Hitler declared this newly established typography to be un-German and declared Fraktur, an archetypal variety of blackletter, as the official typeface of Nazi leadership. Its gothic sobriety was perfect to accompany Hitlers’ Aryans.

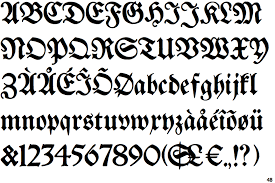

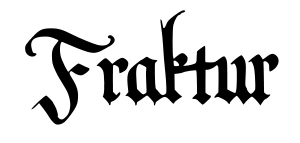

The font Fraktur got its name from its fragmented appearance. The term derives from Latin Frāctūra (“a break”), the same root as the English word ‘fracture'. The harsh angles and broken-up lines that define the letterforms are a prime example of its fractured image, and consequently, how it came to get its name. In German, one of the terms that is often applied to blackletter typefaces is Gebrochene Schrift (“Broken Script”), and Fraktur takes that description to heart. The lowercase characters, instead of being circular or ovular in shape, are built out of various line segments, which results in stricter letterforms that appear to undulate.

Figure 10-11: Fraktur font family

Typography can silently influence: it can signify dangerous ideas, normalize dictatorships, and sever broken nations. In some cases, it may be a matter of life and death. And it can do this as powerfully as the words it depicts.

Fraktur was positioned as a symbol of German national identity and remained in use by Nazi parties where it was represented as true German script. It caused quite the typographic stir. Official Nazi documents and letterheads employed the font and a Nazi minister even forcibly installed Fraktur-ready typewriters in government offices. The shift remained controversial; in fact, the press was often scolded for its frequent use of Roman characters and threatened that papers that printed with anything but German script would be denounced. The Nazi party also used Fraktur within their propaganda to represent the ideology of Nazism – decorative renditions of Fraktur were showcased on posters, the opening credits of Leni Riefenstahl’s chilling propaganda documentary Triumph of the Will (Riefenstahl, 1935) used the font, and a hand-drawn version of Fraktur can be seen on the cover of Hitlers’ Mein Kampf (Hitler, 1925).

Figure 12: Nazi propaganda posters from World War II, using Fraktur Blackletter (German Script)

The Nazi party continued to rise to power on a wave of German chauvinism. And at first, this seemed great for those in favour of traditional blackletter typefaces, which Nazi party officials were promoting heavily at the time. They continued to use Fraktur extensively, but in 1941, it was revealed that Hitler didn’t particularly like the font, and derided Frakturs’ “Romanticism”. The regime needed to re-characterize the font and issued a circular to all the public offices which declared Fraktur to be JudenLetter (Jewish Letters) and systematically prohibited it from further use. In the decree, Hitler argued that blackletter was a Jewish invention and that the long history of Jewish writers and printers had tainted the letterforms – this wasn’t true, but it was an unassailable argument and impossible to come back from, especially given the circumstances at the time. The government of one of the world’s greatest powers banned a typeface. That is the power of a symbol.

At this time, Germany controlled much of Europe. Hitler knew that if he wanted to rule over the world, he would have to use a typeface that the rest of the world could actually read. He claimed that the comparative simplicity of fonts like Antiqua, a roman style font, would help German become the world’s language. The Nazi party ended the controversy surrounding Fraktur in favour of modern, more legible fonts and suddenly Antiqua was everywhere. In keeping with Bauhaus ideals, Antiqua was meant to be a forward-looking typeface – the anti-Fraktur perhaps. But now, Fraktur, nor its cursive counterparts, were to be taught in schools, used in government documents, or appear on street signs. Publishers and printers were informed that no printed matter of any kind could use the typestyle and were expected to change to Antiqua imminently.

Figure 13: Antiqua font, Paul Renner.

As you might imagine, blackletter typography didn’t age well in the post-war period. They became blocky remnants of shame. In just a few years, blackletter went from ordinary to a widespread taboo – the same way that symbols aligned with the fallen regime; eagles, iron crosses and the Totenkopf (Skull and Crossbones) were also eradicated.

Even to this day, Germany holds complications with blackletter. Fraktur has its gothic roots in German identity – an identity that most people now want to forget. Consumer items and commercial ventures often use the font without any trouble by playing up to its medieval qualities, evoking a more innocent sense of tradition - in these cases, it appears invisible - but there are contexts where its use is not as innocent and can’t be forgiven as naïve. Depending on one’s perspective, blackletter can either represent the rich and proud heritage of German cultures, or alternatively, symbolize everything that is wrong with it.

Revival of Blackletter

You might expect blackletter to have become a purely historical footnote in typographic history by now, but this is not the case. The rise of digital technology influenced the modernization of the typestyle, which essentially led to its revival. In the 1990s, during the early years of digital graphic design, font makers were creating new blackletter fonts and digitizing historical ones. These fonts were being manufactured by large companies as well as smaller type foundries and independent type designers.

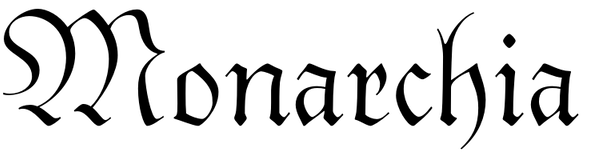

One individual who has made a great contribution to digital blackletter type is Czech designer, František Štorm, founder of Štorm Type Foundry. Although most of the foundry’s releases have been serif and sans serif families, it has also published various variations of blackletters, with Monarchia being Štorm’s most acclaimed piece - A digital revival of Frühling, an influential German typeface designed by Rudolf Koch in 1914, combining elements of both Fraktur and Schwabacher. Štorm has captured the vitality and beauty of Koch’s original typeface, distilling them through his broad-nib writing into something new – using washes, alternates, and ligatures as OpenType functions.

Figure 14: Monarchia font, František Štorm.

Figure 15: Frühling font, Rudolf Koch.

Though blackletter is undergoing a public renaissance, it still almost always feels like an anachronism. But its Old-English charm has become a mark of sophistication for readers – something to notice, something to have an opinion on. Suddenly even people out of the design profession seem to care about its many intricacies. It’s often used to give designs an appearance of authority and tradition, and to create a bold and over-powering impression. The heavily stylized nature of blackletter means designers often sacrifice a bit of legibility, and it’s not always the appropriate choice for every design application, yet adventurous designers feel obliged to challenge this…

Ruud Linssen’s, Book of war, mortification, and love, (2010), is a great example of how designers have negated the conventions of blackletter. The designers at Underware font foundry spent almost a decade designing their contemporary blackletter font, Fakir - available in 5 display fonts, as well as 5 text fonts, making it adaptable and suitable for contemporary readers. The Fakir font families’ newly created letterforms are neither medieval nor traditional in appearance, but still manage to feel like they belong inside the expansive class of blackletter forms designed over the past thousand years. Not only are Fakirs’ letters at home within the blackletter style, but they are also very legible in running body text, something that blackletter is not commonly known for. To prove this, Underware published Linssen’s book completely set in the typeface. The book appears quite different from the manuscripts and historical tomes that come to mind when we think of blackletter - its pages are smaller than those of most medieval books, and the letters of the body copy, set in Fakir Text Regular, are much lighter than the pen-written forms used in the Middle Ages. The term blackletter, after all, may have originated because of its dark letterforms, but these modern renditions prove that not all blackletters have to be dense and heavy, they can also be light and delicate.

Figure 16-18: The Book of War, Mortification and Love (2010), published in Fakir Blackletter.

Although the publication did not lead to a restoration in blackletter typefaces being used for book composition, nor was that the designer’s initial intention, the book is still used as a strong proof of concept that typeface designers often use to this day – inspiring them to create font families with the same level of innovation and versatility as Underware did with Fakir.

Today, blackletter can be seen everywhere. Its strong styling makes sense for its typical use as a flashy display font, often used for important headings, logos, advertisements, and web design, but more recently, it has also become associated with beer labels, heavy metal bands, concert posters and even tattoos. Its style is instantly recognisable and differentiated from more common typefaces; bringing an ornamental quality to the work it is used in, making it perfect for designers to emphasise and promote their material.

I have put this typographic practice to use in my freelance career by designing logos for various companies and painting boards, signs and window designs for several establishments around London. My experience in typography for public and commercial use has given me a higher knowledge of the structural makeup of letterforms and how their aesthetics and design qualities can convey different meanings depending on the location, format and context they are displayed in. One of my favourite examples of my own blackletter work is the boards I created for an iconic venue in East London.

Figure 19-21: Authors hand-drawn bar signs for a music venue in East London.

Designing my own typeface

I have always been captivated by fonts. Constantly noticing them in the world around me. As a designer, I find it fascinating how fonts can be used to communicate a message and evoke certain feelings by simply being a visual representation of text. A typeface as distinctive and unique as blackletter creates a bold statement, provoking an appearance of strength and dignity. And with it being such an accomplished and adaptable font, I believe it has so much more potential to offer graphic designers than the advertising campaign headlines and posters that it is commonly used for today.

For these reasons, I have challenged myself in creating my own rendition of the classic blackletter font. I wanted to create a typeface that commemorates its history and considers the original principles of design that influenced its origin in the gothic period, whilst also showing how a modernization of blackletter can lead to a further resurgence and help it become a progressive, forward-looking font in the contemporary design world.

The Process

Step I: Research

I began by researching further into blackletter, focusing solely on the design, structure, and aesthetic qualities of the typestyle. I searched endlessly, examining every blackletter font I could find, trying to differentiate the elements they consisted of – from the elaborate and decorative swirls to the sharp, fragmented serifs. Some of my favourite modern examples of blackletter which have helped influence my font include: Aviorte, Belong Faith, Lordish, California, Huntly and Catterdale…

Figure 22-27: Existing fonts that have influenced my final design.

Step II: Development

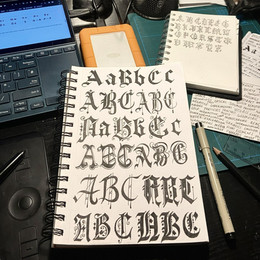

I started sketching out various designs of my own, taking inspiration from blackletters many virtues. After much experimentation, I had created several designs, all considering and incorporating different characteristics of the classic style. I continued to define these further until I reached a comprehensive design with a form and structure that I wanted my font to take and finally achieved a finalised sketch to work from.

Figure 28-33: Authors hand-drawn development sketches for final design.

Step III: Digitizing

Now that I had the basic structure and design of my font in place, I could begin digitizing the full typeface. Using Adobe Illustrator, I meticulously measured out and created a grid to work from, to ensure that the proportion, spacing and kerning of the characters remained accurate and even throughout. I created the base outline of the letterforms using various vector shapes and lines, concentrating heavily on the angular style of the font to make sure each angle peaked at 45 degrees to comply with the traditional conventions of blackletter. I enhanced these sharp letter shapes with elaborate swirls and decorations, to give them the highly stylized appearance rooted in classic medieval calligraphy – and of course, I couldn’t forget the flourishing ascenders on the serifs, extravagantly looping around the caps and further demonstrating its stylized appearance. In addition, I have published this font for public and commercial use, using the templates provided by Calligraphr to do so.

Figure 34-35: Screenshots of digital design process, using Adobe Illustrator.

Final Typeface

Figure 36: Final typeface design

Figure 37: Final typeface design

Figure 38: Infographic breakdown of typeface, visual representation of blackletter traits.

Figure 39: Close up of typeface characters, in different forms

Figure 40: Typeface using Calligraphr template, to create a written text file format for public use.

Conclusion

Blackletter is a hugely influential font and holds a rich and fascinating cultural significance for designers. It has undergone a substantial transformation throughout the centuries - with its origins being traced back to the Middle Ages, where it was used extensively in religious and legal texts, to its dramatic decline during World War II due to its association with Nazi Germany. But blackletter script has seen a resurgence in recent years, with contemporary designers and typographers experimenting with its forms, making it a statement piece for any design project. The revival of blackletter is a testament to its enduring appeal and versatility as a script.

My research has provided an in-depth look into the world of blackletter typography, and accompanied by the design of my own typeface, serves as a great example of how blackletter can be used in modern design practices and positively contributes to the field of typography and design.

The final form of my font has achieved what I originally set out to do – the extravagant swirls and serifs that decorate the characters are a perfect way to commemorate the creation of blackletter from its calligraphic background, whilst the sharp letterforms act as a reminder of its relation to German identity – something that played an integral role in the history of blackletter and shouldn’t always be forgotten. As well as incorporating references to its history, I’ve also adhered to the appeals of the contemporary design world, by favouring a minimalistic style and approach. I believe that my typeface further demonstrates the continued relevance of this historic script and is a great addition to its contemporary revival.

External Links:

Original Progress Map (previous topic): https://padlet.com/mareamaloney/Surrealism

Portfolio / website: https://www.mareamaloney.com/

Bibliography

Websites / online articles

Newton, Gerald (2003) Deutsche Schrift: The Demise and Rise of German Blackletter. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1468-0483.00252 (Accessed: 22 November 2022)

Wikipedia (Date Unknown) Blackletter Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackletter (Accessed: 22 November 2022)

Farley, Jennifer (2009) The Blackletter Typeface: A Long and Coloured History. Available at: https://www.sitepoint.com/the-blackletter-typeface-a-long-and-colored-history/ (Accessed: 24 November 2022)

Aviram, Adí (2021) In With the Old: Designing With Old English Font. Available at: https://www.vectornator.io/blog/old-english-font (Accessed: 24 November 2022)

Wikipedia (Date Unknown) Fraktur Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fraktur(Accessed: 29 November 2022)

Siebert, Jurgen (2006) Fraktur ist (auch) eine Nazi-Schift (Translate: Fraktur is (also) a Nazi typeface). Available at: https://www.fontblog.de/fraktur-ist-auch-eine-nazi-schrift/ (Accessed: 29 November 2022)

Typeroom (2020) A Nazi font banned by Nazis? Fraktur and its legacy. Available at: https://www.typeroom.eu/a-nazi-font-banned-by-nazis-fraktur-legacy-must-listen-design-podcast (Accessed: 1 December 2022)

Fitzgerald, Ali (2018) The Rise and Fall and Return of the Fraktur Font. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-rise-and-fall-and-return-of-the-fraktur-font (Accessed: 1 December 2022)

Hersh, Ben (2017) How Fonts Are Fuelling the Culture Wars. Available at: https://www.wired.com/2017/05/how-fonts-are-fueling-the-culture-wars/ (Accessed: 1 December 2022)

Chung, Natalie (2017) Fette Fraktur Typeface. Available at: https://medium.com/fgd1-the-archive/fette-fraktur-typeface-1850-6caf8b0b097e (Accessed: 1 December 2022)

99 Percent Invisible (2020) Fraktur. Available at: https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/fraktur/ (Accessed: 1 December 2022)

Stock-Allen, Nancy (1999) A Short Introduction to Graphic Design History. Available at: http://www.designhistory.org (Accessed: 2 December 2022)

Akander, Deyemi (2016) Architecture and Ornamentation of Gothic Cathedrals. Available at: https://www.sah.org/community/sah-blog/sah-blog/2017/05/08/awe-chitecture-and-ornamentation-of-gothic-cathedrals (Accessed: 7 December 2022)

Brooks, H. Allen (2016) Travelling Fellowship. Architecture and Ornamentation of Gothic Cathedrals. Available at: https://www.sah.org/community/sah-blog/sah-blog/2017/05/08/awe-chitecture-and-ornamentation-of-gothic-cathedrals (Accessed: 7 December 2022)

Hurt, William (Date Unknown) Age of Armour. Basics of a Gothic Font. Available at: https://www.ageofarmour.com/education/font.php (Accessed: 7 December 2022)

Art Fund (Date Unknown) The Psalter and Book of Hours of John Duke of Bedford. Available at: https://www.artfund.org/supporting-museums/art-weve-helped-buy/artwork/816/the-psalter-and-book-of-hours-of-john-duke-of-bedford (Accessed: 11 December 2022)

Raykova, Lora (Date Unknown) The Hidden Story of Gutenberg’s First Typeface and Bible Typography. Available at: https://www.fontfabric.com/blog/gutenberg-first-typeface-original-bible-typography-used/ (Accessed: 14 December 2022)

Nawafleh, Hala (2019) Major Influences on Gothic Architecture. Available at: https://issuu.com/halanawafleh7739/docs/___________/s/12292985 (Accessed: 6 January 2023)

Typotecture (2011) Gothic Architecture + Blackletter Type. Available at: https://typotecture.wordpress.com/2011/08/01/gothic-architecture-blackletter-type/ (Accessed: 9 January 2023)

Rainis, Jake (Date Unknown) The History of Blackletter Calligraphy. Available at: https://jakerainis.com/blog/the-history-of-blackletter-calligraphy/ (Accessed: 12 January 2023)

Adobe Fonts (Date Unknown) Blackletter. Available at: https://fonts.adobe.com/fonts?browse_mode=default&cc=true&max_styles=26&min_styles=1&ref=tk.com&referrer=dd01e5bd12&tag=blackletter (Accessed: 12 January 2023)

Reynolds, Dan (Date Unknown) Blackletter Today. Available at: https://www.commarts.com/columns/blackletter-today (Accessed: 13 January 2023)

Storm Type Foundry (Unknown) Available at: https://www.stormtype.com/ (Accessed: 13 January 2023)

Underware (2010) The Book of War, Mortification and Love. Available at: https://www.underware.nl/publications/the_book_of_war_mortification_and_love/ (Accessed: 23 January 2023)

Calligraphr (Date Unknown) Available at: https://www.calligraphr.com/

Books

Krysinski, Mary (2017) The Art of Type and Typography: Explorations in Use and Practice.

Bringhurst, Robert (1992) The Elements of Typographic Style.

Cole, Teju (2021) Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time.

Ambrose, Gavin and Harris Paul (2006) The fundamentals of Typography.

Bertheau, Philipp (1998) Blackletter: Type and National Identity.

Victionary (2022) Hand Lettering: 20th Anniversary Edition: From Calligraphy to Typography.

Solo, Dan (2003) Gothic and Old English Alphabets: 100 Complete Fonts.

Linnsen, Rudd (2010) The Book of War Mortification and Love

Hitler, Adolf (1925) Mein Kampf

Film

Triumph of the Will (1935) Directed by Leni Riefenstahl [Documentary]

Podcast

99 Percent Invisible (2020) Fraktur: Episode 390. [Podcast] 18 February. Available at: https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/fraktur/transcript/

List of Illustrations:

Fig. 1-2: Authors own (2022) Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris. Details of architectural and sculptural decorations on the western façade. [Photograph]

Fig. 3-4: Plantagenet, John (c.1422) The Psalter and Book of Hours of John Duke of Bedford. [Illuminated Manuscript] Available at: https://www.artfund.org/supporting-museums/art-weve-helped-buy/artwork/816/the-psalter-and-book-of-hours-of-john-duke-of-bedford

Fig. 5: Nawafleh, Hala (2019) Architectural ogival arch with gothic influence. [Illustration] Major Influences on Gothic Architecture. Available at: https://issuu.com/halanawafleh7739/docs/___________/s/12292985

Fig. 6: Authors own (2023) Illustrated depiction of architectural influence on typography. [Illustration]

Fig. 7-8: Raykova, Lora (Date Unknown) Johannes Gutenberg 42-line Bible and accompanying letterforms, Donatus-Kalender. [Design and Photograph] The Hidden Story of Gutenberg’s First Typeface and Bible Typography. Available at: https://www.fontfabric.com/blog/gutenberg-first-typeface-original-bible-typography-used/

Fig. 9: Wikipedia (Date Unknown) The four major blackletter font families; Textura, Rotunda, Fraktur and Schwabacher. [Design] Blackletter Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackletter

Fig. 10-11: Brietkopf, Johann (c.1800) Fraktur Font family. [Design] Fraktur Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fraktur

Fig. 12: Siebert, Jurgen (2006) Nazi Propaganda posters from World War II, using Fraktur. [Posters] Font Blog. Available at: https://www.fontblog.de/fraktur-ist-auch-eine-nazi-schrift/

Fig. 13: Renner, Paul (1939) Antiqua Font. [Design] Antiqua-Fraktur Dispute Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antiqua%E2%80%93Fraktur_dispute

Fig. 14: Štorm, František (2005) Monarchia font. [Design] Storm Type Foundry. Available at: https://www.stormtype.com/families/monarchia?utf8=%E2%9C%93&pangram=3

Fig. 15: Koch, Rudolf (1914) Frühling Font. [Design] Fonts in Use. Available at: https://fontsinuse.com/typefaces/32487/fruehling

Fig. 16-18: Underware (2010) The Book of War, Mortification and Love, published in Fakir Blackletter. Underware. Available at: https://www.underware.nl/publications/the_book_of_war_mortification_and_love/

Fig. 19-21: Authors own (2022) Hand-drawn bar signs in a music venue in East London, signs for commercial use. [Photograph]

Fig. 22-27: Moran, Matt (2023) Best Blackletter fonts. [Design] Design Bombs. Available at: https://www.designbombs.com/best-blackletter-fonts/

Fig. 28-33: Authors own (2023) Hand-drawn development sketches for final design. [Photograph]

Fig. 34-35: Authors own (2023) Screenshots of digital design process, using Adobe Illustrator. [Photograph]

Fig. 36: Authors own (2023) Final typeface design, layout 1. [Design]

Fig. 37: Authors own (2023) Final typeface design, layout 2. [Design]

Fig. 38: Authors own (2023) Infographic breakdown of typeface design, used as a visual representation of Blackletter traits. [Design]

Fig.39: Authors own (2023) Close up of final typeface, in different forms [Design]

Fig. 40: Calligraphr (2023) Authors designed typeface in a calligraphr template, to create a written text file format for public use [Design] Calligraphr. Available at: https://www.calligraphr.com/en/webapp/app_home/?/fonts

Comments